The Muslin of Bengal

SHARE

“The cloth is like the light vapors of dawn.” — Hiuen Tsang, Chinese traveler to India.

It is, but it is not. It is on your body, but nobody can see it. You can feel it, but it’s invisible to others. What is it?

Relax. You don’t have to rack your brains. This isn’t some tricky metaphysical stuff that we are discussing here. It’s a textile, a very special textile. We call it Muslin, and its story goes a long way back in history.

The fabric was so special that there were reports that it wasn’t man-made at all. Some said it was the handiwork of fairies. Others said it was turned out by ghosts and handed over to a select few. There were still others who thought Muslin was thrown up by creatures inhabiting the subterranean realm.

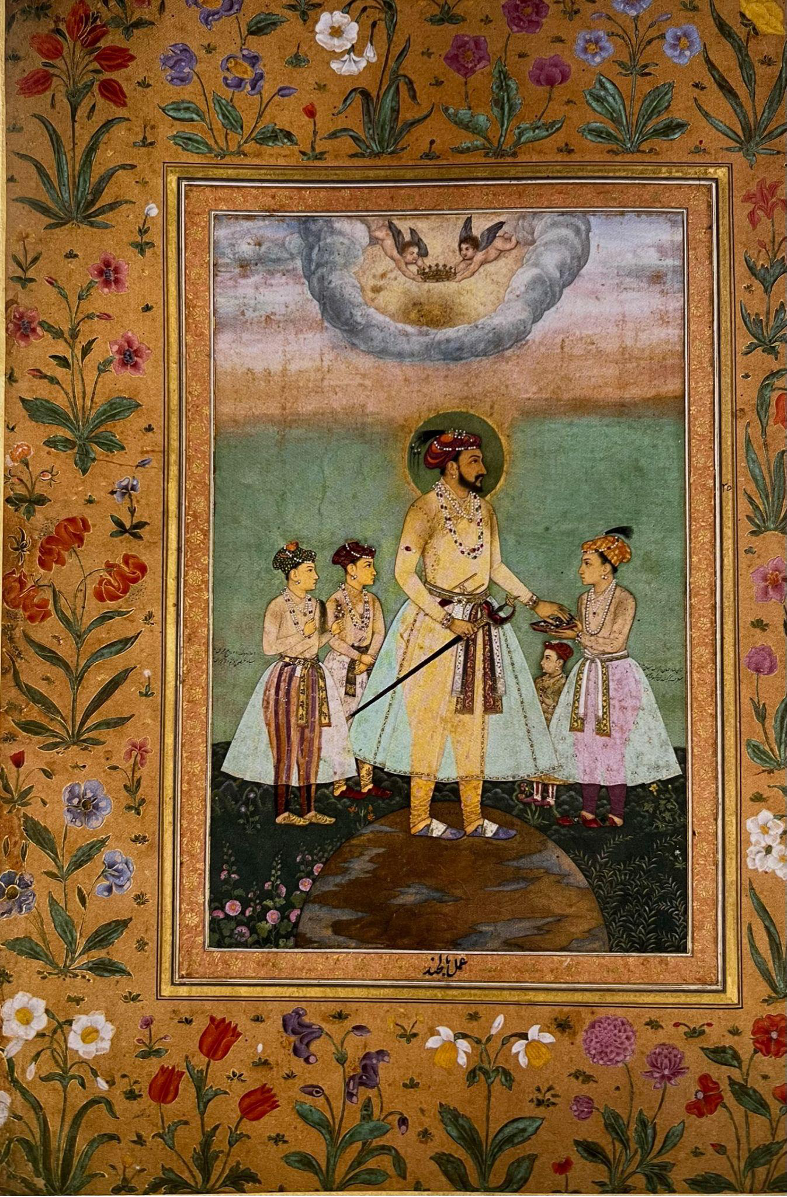

(Shah Jahan with his four sons. Notice the translucent Muslin fabric)

All these exciting theories notwithstanding, Muslin was very much the product of human labour — or, to put it more precisely, it was the product of the efforts put in by the people inhabiting the region called Bengal, today divided between Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal.

The production of Muslin was tricky, involving almost two dozen steps and the dedicated focus of another few dozen human beings. The plant itself was notoriously endemic, refusing to grow anywhere apart from a short stretch along the Meghna river. It had to be harvested as carefully as a mother watches over her sick children.

Then, the balls of cotton had to be cleaned with only one peculiar implement: the jawbone of a particular fish that, apart from being cannibalistic, isn’t most innocuous towards humans either. Next on the list was spinning. This process required a high degree of humidity, so women would stay up all night plying their needles on dinghy boats to make sure the fine fibres took shape. Finally, there was the weaving. The designs favored by the elite consumers — mostly geometric shapes depicting flowers — had to be integrated directly into the cloth, a process that could continue for several months on end.

The product of such elaborate efforts was a textile that was so flimsy that, in the words of the famous poet Amir Khusrau, “it looks as if one is in no dress at all but has only smeared the body with pure water.” There were times, however, when its ultra-fine quality landed Muslin in some trouble. When Nero was living it up in Rome, his courtier Petronius sneered on the transparency of Muslin, calling it a lewd garment that did nothing to conceal a woman’s nudity.

Then, the grapevines report that Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb almost tripped once when he saw his adult daughter roaming about naked. Fuming, he asked his daughter what occasioned her nude parade. His daughter protested that far from being naked, she was wrapped in as many as seven layers of Muslin. Aurangzeb was deflated: Muslin was just being Muslin, he must have thought.

Far more serious than these family tiffs was the row that Muslin triggered in 18th-century Europe, when an entire social class was accused of deliberately appearing in public naked. As the trade with India picked up pace, the inflow of Muslin into Europe turned from a trickle to a deluge. In the UK, the clunky dresses of the Georgian era were out in a trice, and Muslin became an instant hit among those who could afford them. The puritans took umbrage at this, and a popular English magazine featured a tailor telling his female client that it was far better to simply go about naked than shell out pounds for a muslin dress which, at any rate, did little better to conceal nudity. Things were hardly better across the English channel in France, where satirists and cartoonists spared no effort to lampoon Muslin and its patrons: a super elite coterie that included such personages as Marie Antoinette and Josephine Bonaparte.

The scandal that rocked Europe, incidentally, was the last major controversy the Muslin found itself in. No, society didn’t become super progressive all of a sudden. Controversies ceased … because, well, Muslin itself ceased to exist. British rule over India spelt ruin for much of what India was globally famous for, and the worst hit was the Muslin industry.

As traders turned rulers, prices came to be dictated at the point of sword. The fabulous Muslin textiles, for which the Mughal royalty was once willing to spend a fortune, was now forcibly bought off for a pittance trifle.

Finding the new terms too unfavorable, the craftsmen started giving up their craft, a development the British were only too willing to encourage — after all, wasn’t this an easy way to ensure that the cloths churned out by the mills in Lancashire did well in the market?

Thus ignored, Muslin quietly receded into the pages of history. By the beginning of the twentieth century, Bengal Muslin had disappeared from every corner of the globe, with the only surviving remains safely tucked away in private collections and museums. The convoluted technique of making it was forgotten, and the only type of cotton that could be used — locally known as Phuti Karpas — was found extinct.

Today, in Bangladesh at least, efforts are on to bring back the lost wonder, and some of the results that have come up do look promising. Reaching the pre-colonial level of finesse, however, is still a long way off. Most versions made today have thread counts — representing the number of crisscrossed threads per square inch — somewhere between 40 and 80. The Muslins that draped the Mughal royals, by contrast, had a stratospheric thread count of around 1200.

#BengalMuslin #MughalHistory #IndianFabric #History #Textile #Bengal

Author @nawabchaterjee